Recently, my wife and I spent a day (sans children) hiking on Isle Au Haut, a 10 km ferry ride from Stonington, ME. Isle Au Haut has about 45 year-round residents, and much of the island is part of Acadia National Park. Due to it’s remoteness, it’s the least visited part of Acadia (actually, I don’t have any data on that, but I’d bet you a nickel it’s true). There are only two rangers on the island and part of their job (aside from being incredibly friendly and knowledgeable) is to make sure everyone that entered the park in the morning leaves at the end of the day on the last ferry.

This will be the first of several posts on the trip, and I’ll include a photo or two with each post.

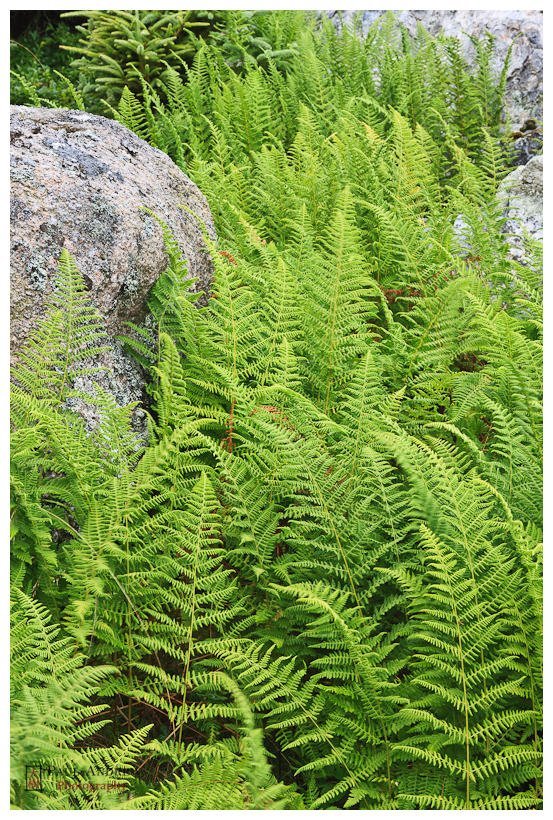

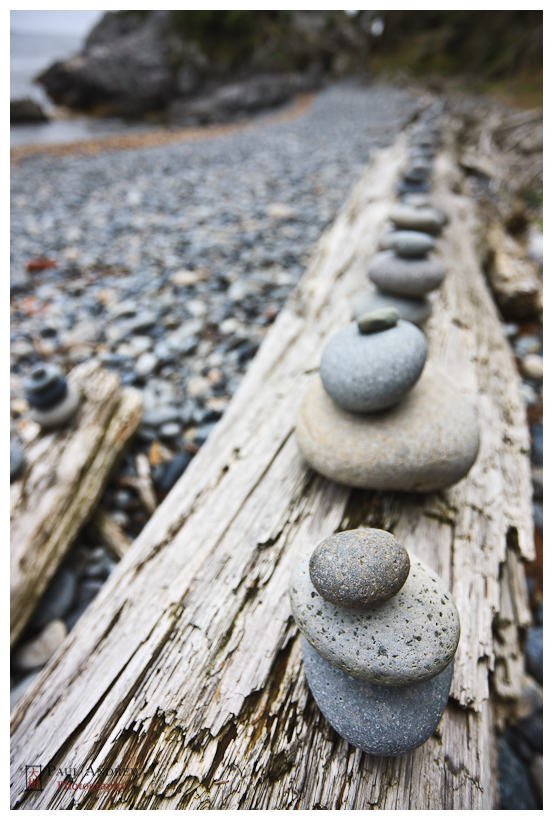

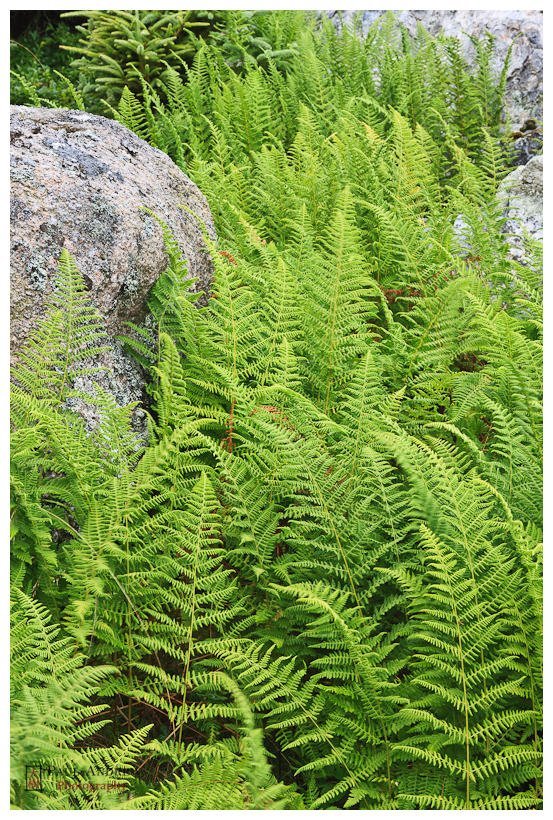

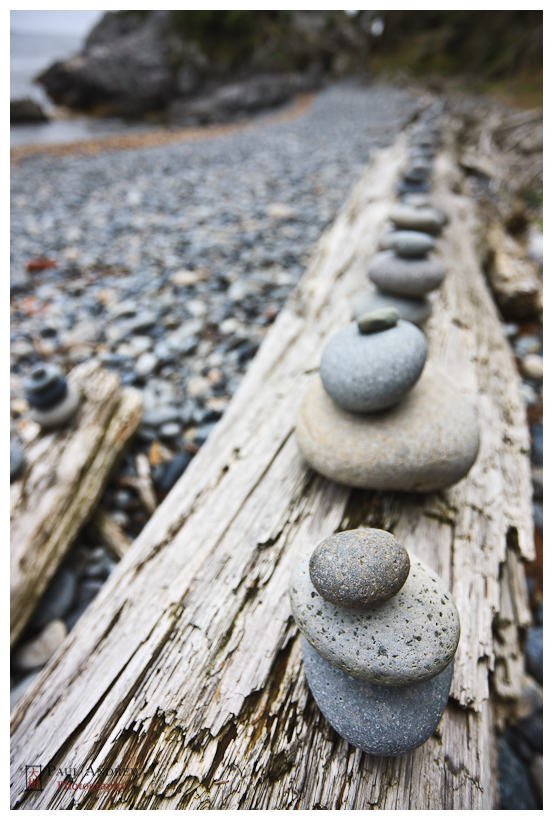

Today’s photos, the ferns (A) and the beach rocks (B), are taken at Duck Harbor (southwestern part of the island), and Squeaker Cove, respectively.

Duck harbor was where I first noticed that Isle Au Haut has some of the largest uninterupted fields (except for large boulders and occasional trees) that I have ever seen. These fields are so densely packed with ferns (I believe in this case, hay-scented ferns) that they seem to have crowded out many other species of plants. The visual effect is amazing, and the soft overcast light made photographing the fields quite pleasingly simple.

After a short hike up and over Duck Harbor Mountain, we arrived at Squeaker Cove. Beautiful smooth granite stones line the beach, which inevitably prompts people to create little cairn scultpures, many of which you can see here.

Incidently, when we arrived at the next beach at Deep Cove, which is populated by similarly smooth granite stones, my wife stepped in such a way that two of the polished stones slid against each other and produced a noise we both spontaneously described as a squeak, hence our theory that this is behind the naming of Squeaker Cove.

I have no idea if this theory has any truth to it, but it’s a good sounding theory. So there.

I hope you enjoy the images. More about hiking on the island in the next post.